The discovery of the Digital Scrolls caused quite a flurry among the Guild of Human Historians, mitigated marginally by the time it took to extract and translate the data. Then came the task of grouping texts and assigning them to research teams, accompanied by the usual bureaucratic bottlenecks and requisite hierarchical pissing contests.

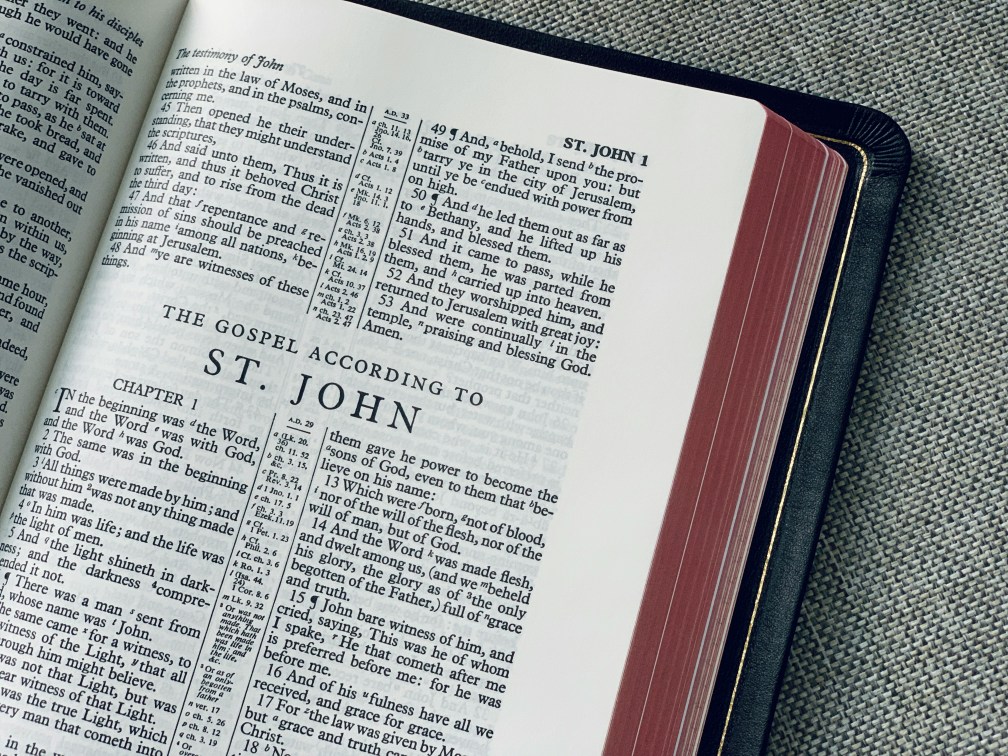

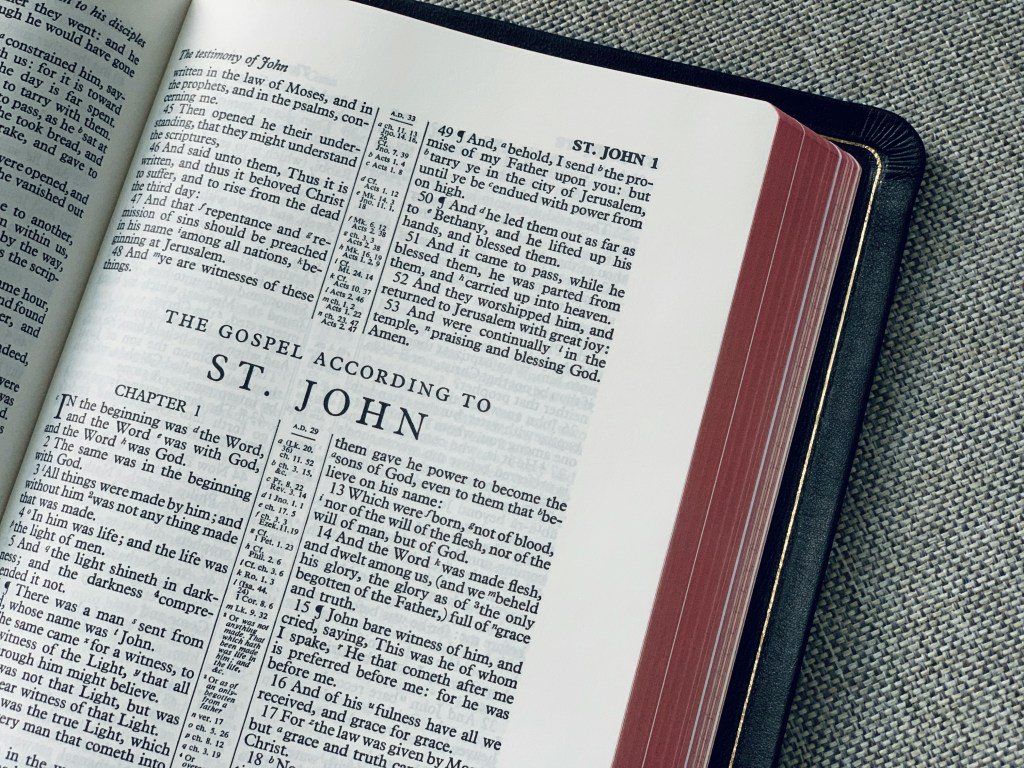

Junior Guild members such as myself were assigned the least important pieces—isolated and/or anachronistic fragments of texts that resisted classification. I was tasked with working on a few lines from an arcane segment called ‘John’s Gospel.’ That its digital trace was identified in the Scrolls dated it to the dawn of the Anthropocene, but a cursory comparison with supposedly contemporary data suggested an even earlier origin.

Something about the document transfixed me.

‘I think it’s a sacred text,’ I told my supervisor, Jim. I translated the first line for him.

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with the Creator, and the Word was the Creator.

Jim’s chair squeaked as he shifted to hide his yawn. ‘The Word is language, I presume,’ he said, dully, and I understood his indifference. If ancient humans put language as the origin of all existence, their beliefs would not be dissimilar to ours, and there would be no story.

‘Most likely,’ I said. ‘But I don’t think they meant the Earth’s language. When they say Creator, I don’t think they’re talking about the Earth.’

Jim turned to face me, his eyebrows raised. The chair squeaked again, as if to protest such a heresy.

‘What other language would there be, other than the Earth’s? What other Creator?’

‘I think,’ I ventured, swallowing, ‘that they saw their Creator as existing outside of the Earth. Above the Earth, even. And they knew no other language than human language. They believed their language came from this other, human-like god.’

Jim’s eyes locked on mine. The implications of such a belief system were hard to imagine. A final, decisive squeal from his chair jolted him from his rumination. ‘Nonsense,’ he concluded. ‘If ancient humans believed such a thing, they never would have survived. They’d have been crushed by the weight of their own suffering.’

I left Jim and returned to the ever-elusive John’s Gospel, marvelling at our ancestors, whose god was so other, whose language was so separate, whose suffering was undeniably fathomless.

Would you like to know more about this story? I discuss it in Episode 107 of Structured Visions. You can also sign up to the Grammar for Dreamers newsletter to get monthly updates on the ideas that inspire my work.