Who are all these people, and why are they all here?

Belinda has not responded to her three-year-old daughter’s repeated questions, though the answers are easily available.

The beach house seems ready to burst at the seams, either from the heaving throngs of family sprawled about in various stages of multi-family chaos within, or from the howling gales that hammer against the paper-thin walls without.

These are my cousins, and they’re here for your great-grandmother’s funeral.

They’ve reached that drunken stage of family gathering where everyone tries to remember Nan’s stories.

Bill, once the thick-headed bullying eldest cousin, now professor of comparative literature at Boston University, tries to convince everyone their grandmother’s vast collection of stories consisted solely of variations on Bible themes.

Carly, who runs a tattoo salon in Brooklyn says he’s reading way too much into it.

Gina, the Montessori peacekeeper, is praising the artichoke dip.

Who are all these people, and why are they all here?

Belinda has breathed barely a word since they congregated at the family vacation home, not even to her daughter – just enough to manage the logistics of getting Ella fed and tucked into the cot in their shared room. She’d like to be in bed herself, but can’t risk it yet. Ella sleeps lightly and might hear her crying.

Bill reminds Carly that Nan was once a nun, and professes his belief that the endless stories were her rebellion against the church and its narratives.

If she was that pissed off about the church, why are we burying her in one, Carly wants to know, and Gina pipes up that there was one story in particular that reminded her of Noah’s ark.

‘The story Nan told was about a man named No.’

The words have escaped Belinda’s lips as a breathy whisper, but the wind has just ceased, and everyone’s heard her. The cousins and their partners stay silent, waiting for more.

Who are all these people, and why are they all here?

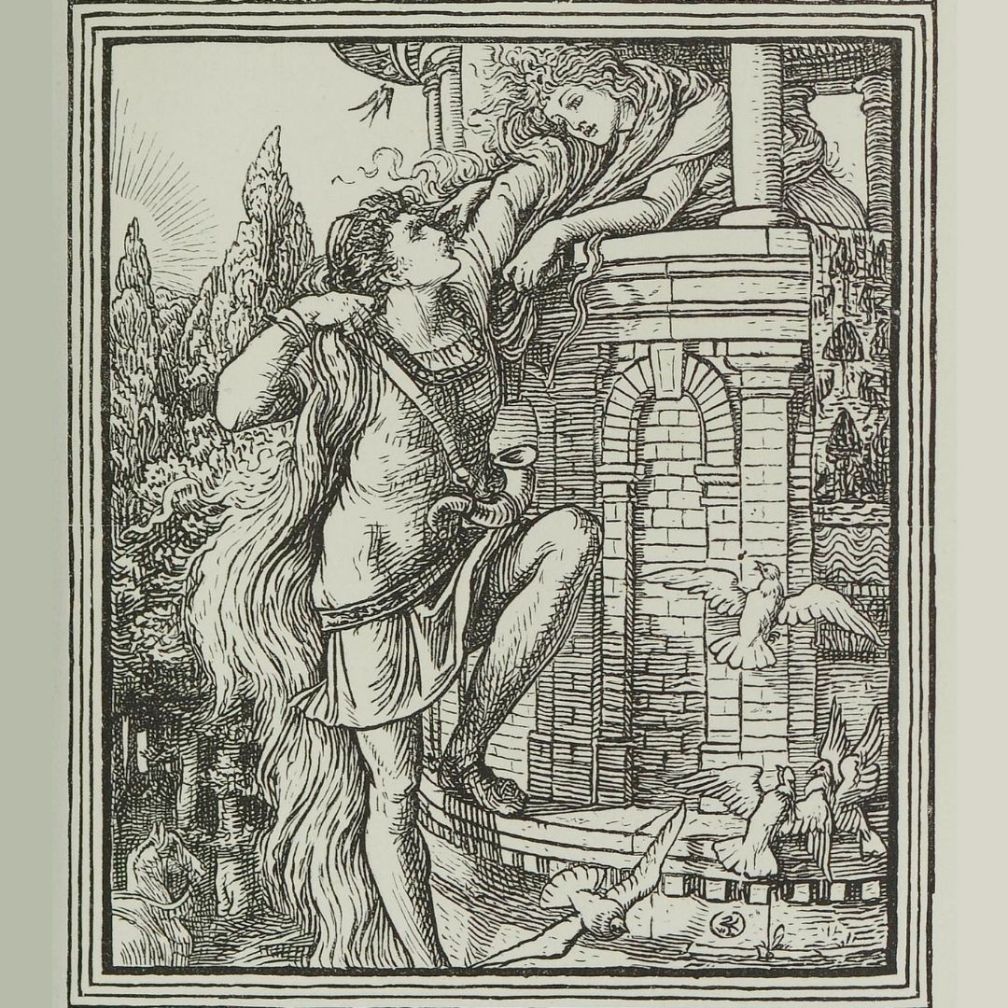

‘No was the only person on the Earth. He lived among all the animals, who named him “No” because he had no speech. No matter how much they simplified their language, he could never make sense of what the animals were saying. He just kept shaking his head, “no”.’

They’re your family, and they’re here because my Nan died.

What would Ella know of people gathering when someone died? Greg died suddenly, in the middle of the pandemic, and they weren’t allowed a funeral. What Ella knows of her own daddy’s death is loneliness and silence, not this expansive hearthside festival of laughter and story.

Belinda shakes her own head, ‘no’, at her cousins’ clear desire to hear the rest of the tale. Still, the words tumble out, as relentlessly as the newly revived winds.

‘The animals got together and decided No was too distracted by all the beautiful things on the land, so they called down the rain to wash it away. They built a boat and drifted away on the monotonous sea. For forty days and forty nights they taught him their language.

‘No remained silent, confused.’

Her family had tried various ways to contact her, to keep her company during her grief, to occupy Ella, to encourage Belinda to go out for a walk at least to clear her head. Belinda turned off her phone and retreated inside herself, silent. Ella stopped crying, and Belinda’s own tears remained voiceless, wracking, heaving.

‘When the rains stopped and the waters finally abated, the animals gave up hope. They moved back to the dry land in the springtime and made their dens there. No did not follow them.’

It’s a strange place for the story to end, but Belinda cannot remember any more.

No must have died alone on the boat, starved by his own silence.

Perhaps he found peace at the end.

‘In the silent nights, No’s ears were opened,’ she’s saying now, finishing the tale. She can hear her crazy grandmother’s soothing tones of her voice in her own voice. She puts her arms around herself and keens slowly, more than a little crazy herself by now, she imagines.

‘No’s ears were opened to the whistling tunes of the wind. His heart beat to the staccato rhythms of the waves drumming the boat’s resonant hull. He swallowed the wind and the waves, and at once he had language.’

But it was not a language the animals knew, and No remained alone.

The tragic ending of her grandmother’s tale remains unvoiced, except by the wind that still beats insistently against their mourning house.

Would you like to know more about this story? I discuss it in Episode 73 of Structured Visions.