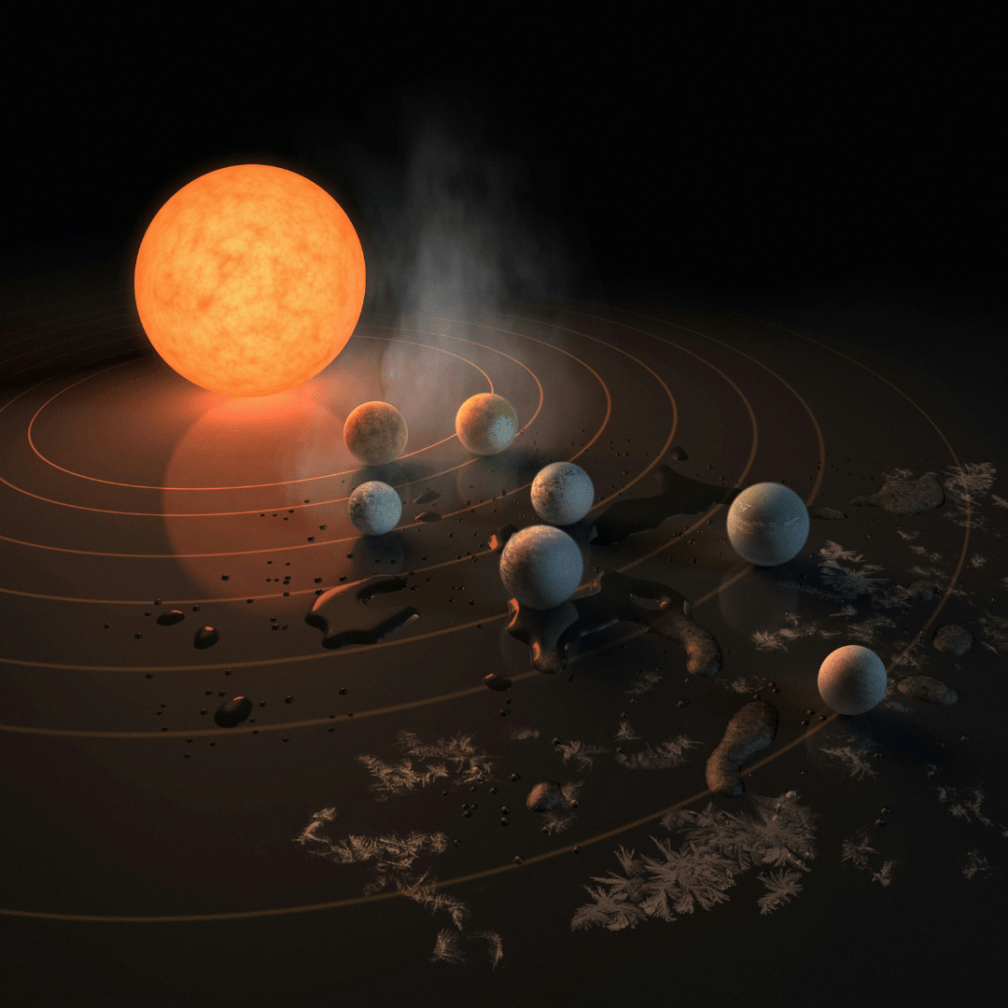

A report for the life-sustaining planets of Trappist-1, in partial response to queries about introducing the consciousness-restrictor known as ‘restricting language’ into their ecosystems

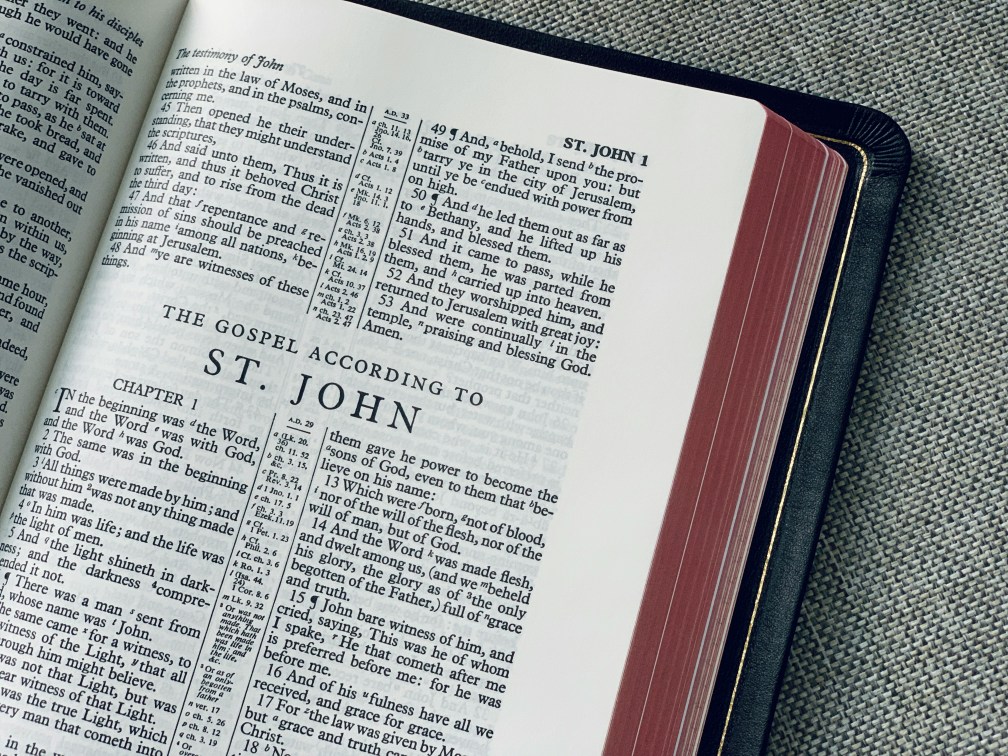

On the Earth so far the only creatures to be infected with Restricting Language (henceforth RL) are a group of hominids, specifically the extant species within the Homo genus, known as sapiens. One notable symptom has presented as bipedalism, which distances the human body from the surface of the Earth, thus reducing its capacity to absorb the planet’s generosity and intelligence. RL seems to have simultaneously prevented the development of feathers or wings present in other bipedals, which give the latter access to the embrace of the Earth’s atmosphere.

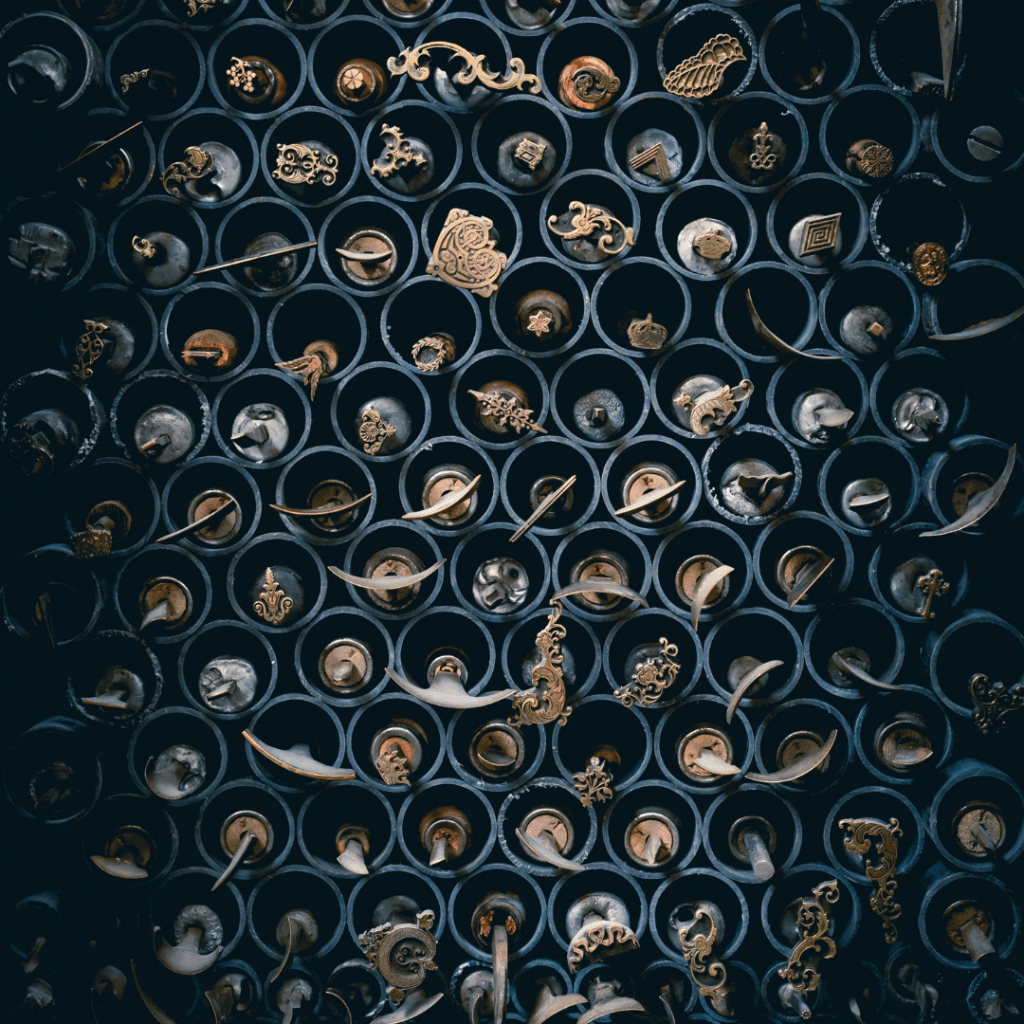

The RL-infected bodies produce flexible fingers and opposable thumbs, but they rarely apply their hands as a means of self-propulsion over land or through trees. Nor do Homo sapiens make use of the prehensility of these extremities for connection with the Earth. They grasp not the Earth’s ideas, but their own, clinging, gesturing, tapping at machines.

RL has stripped human bodies of fur, feathers or leathery armour, leaving only ineffectual vellus hair. Believing they have lost the Earth’s protection, Homo sapiens cover themselves in clothing made from animal, plant or artificial material.

A key finding is that RL infection cuts bodies off from reality. Human brains have adapted by swelling their prefrontal cortices to increase the capacity of their delusions. RL-influenced thoughts are marked by separateness, loneliness, longing.

Only when they sleep do these bodies, stretched prostrate, surrender. The infection eases. The lungs expand in relief. The Earth’s soothing wisdom pulses through their dreams.

Would you like to know more about this story? I discuss it in Episode 113 of Structured Visions. You can also sign up to the Grammar for Dreamers newsletter to get monthly updates on the ideas that inspire my work.