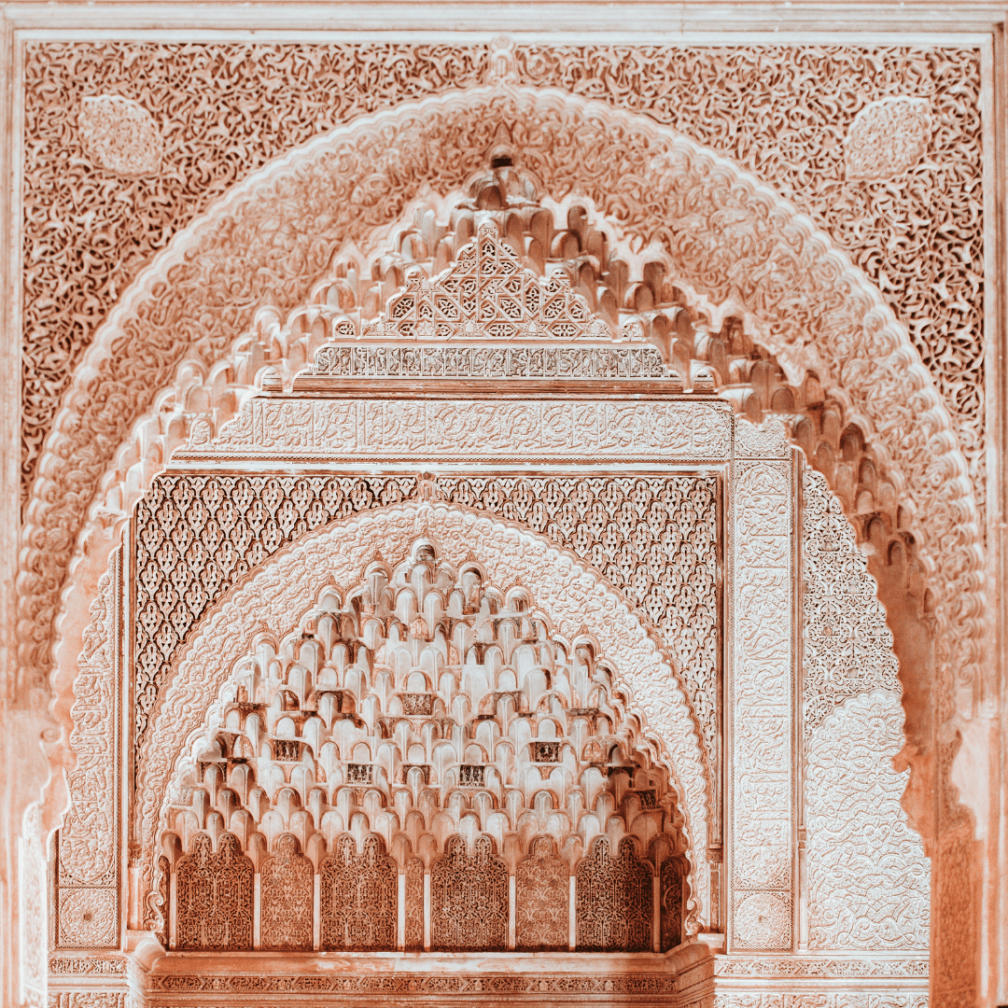

It was a beautiful piece, entirely unique, rosewood carved in an intricate labyrinthian latticework. The woodcarver held the egg-shaped sculpture in the nest of his open palms, as if beckoning Aimee through the bewildering chaos of scents, sounds, colours and textures of the Marrakech souk.

‘C’est quoi?’ she asked.

A toothless smile illuminated the seller’s ancient face. ‘Un calendrier d’Avant,’ she thought she heard him say, or perhaps, ‘Un calendrier de langue’. The latter was more probable in a Muslim country, she reasoned, and indeed, each willow-like branch was engraved with a delicate looping script, maybe some form of Arabic calligraphy.

But back home, she discovered tiny doors hidden within the interior of the egg, each numbered in the same elegant script, one to 24, closed tight in anticipation for the proper season.

So with great patience she waited for December, and a childlike ceremony presided over the unlatching of the first door on the first of the month.

Her initial disappointment was assuaged by the captivating polished smoothness of the empty space. She stroked the wood hypnotically, imagining what treasure might have been lovingly tucked inside. A tiny bauble, a miniscule vial of spice, a line of poetry on a strip of delicate rice paper.

Subsequent days found her snaking her exploring hand into the complex networks of carved wood. Each opened door revealed a void in miniature, with just enough room for her probing fingertip. No treasures but space, no gifts but emptiness.

On Christmas Eve, the ritual complete, Aimee decided it was never a ‘calendrier d’Avant’ and always a ‘calendrier de langue’. She traced a loving finger around the smooth, welcoming spaces hidden behind the doors of language, as if conjuring the exquisite gifts that could be held within.