The homeless guy was naming things.

This was my big revelation.

It took a month’s worth of visits to the laundrette to work it out.

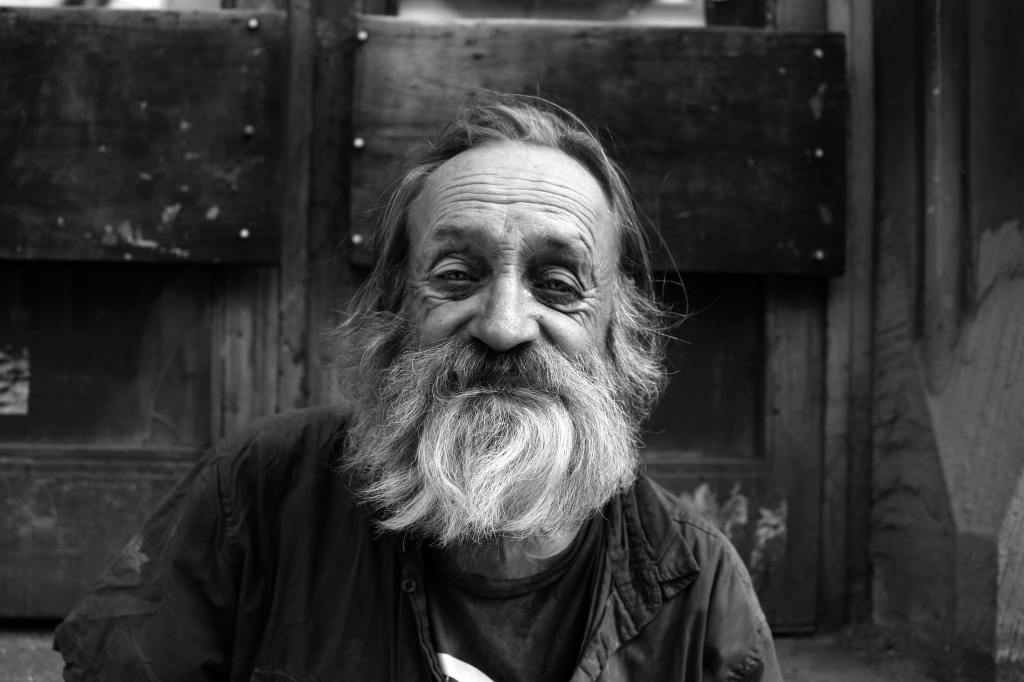

On Saturday of week one I had no idea at all. I was consumed with my abysmal turn of fortune—my own washing machine damaged beyond repair, my kitchen flooded and clothes likely ruined. I hauled the sopping load through bitter cold rain to Sudsarama on Market Square. The tramp was settled in so comfortably in the room’s wet, fragrant heat that at first I didn’t even notice he was there.

He did not afford me the same courtesy.

‘They’re spinning,’ he croaked.

I did not need to make eye contact to know he was talking about the thrumming dryers. I nodded as politely as I could manage.

On Saturday of week two I was nearly out of underwear and entirely out of patience. My new washing machine had been held up at the warehouse. I made my reluctant pilgrimage to Sudsarama, heavy laden with shopping bags filled with smalls.

The tramp sat sedately in the same spot as the week before, like a priest of the oracle.

‘They’re helping,’ he said.

I followed his gaze to a woman outside walking her dog. The latter sported a hi-vis vest that endorsed its support-animal status.

I kept my gaze focused just beyond the window for fear of being drawn into some maddening conversation.

Still, I couldn’t help but be curious about what sort of assistance my homeless companion thought the human-canine pair was providing, and to whom.

‘They’re helping?’ I asked.

To my surprise the objects of our discourse opened the door and entered into the Sudsarama shrine.

‘They’re helping,’ the tramp affirmed. He leant down to scratch behind the dog’s ears and whisper into them. ‘They’re spinning,’ he told the dog, pointing his gentle chin toward the dryers.

By week three, I’d formed a few hypotheses.

The tramp used the plural pronoun for everything, even singular referents, like the dog.

He was too polite to make assumptions about people’s pronouns. Or dogs’ pronouns. Or dryers, for that matter.

And the -ing words—spinning, helping—the tramp wasn’t using them as verbs.

They were names.

He’d named the dog ‘Helping’, and the dryer ‘Spinning’.

No, he hadn’t named them—suddenly it was somehow clear to me—he knew their names already, he was simply stating what was true.

Everything he encountered already had a name, a name that revealed the entity’s essential quality, and the name of everything was a verb.

On the fourth Saturday I decided my duvet needed a clean and that my newly installed washing machine wasn’t big enough for the job. I raced across the square, fixated upon the plate glass windows of Sudsarama and whether my guru would appear through them.

When his shadowy figure came into focus I felt something release in my chest, like an unacknowledged longing spreading its wings to take flight.

I leant against one of the dryers and gazed shamelessly into the man’s weathered eyes. ‘They’re Spinning,’ I said.

With his nod I felt a wave of compassion wash over me.

‘And him-’ I said, pointing to a terrier running free on the street, who’d stopped to cock his leg on the lamppost opposite. ‘Them, I mean. They are-’

‘They’re Helping,’ he said.

I made a mental note: All dogs are Helping.

‘And those?’ I asked, flinging my pointing arm wildly toward the fountains in front of the City Hall.

‘They’re Flowing.’

‘And those?’ I pointed to the semi-circle of bare-branched cherry trees that framed the water feature.

‘They’re Breathing.’

I could no longer speak, only stand in awe of the man’s wisdom and the grace with which he bequeathed each thing with his essential quality, its name.

‘And me?’ I begged when I finally found my voice, thumping my chest, a frenzied chimpanzee. ‘Who am I?’

His silence precipitated a gaping despair at the heart of me, like a landslide on the edge of a vast abyss.

In a desperate attempt I tried again.

‘These?’ I hadn’t stopped drumming on my sternum, so urgent was my need to know. ‘What are these?’

His lips fluttered as if brushed with the briefest of smiles.

‘They are Being,’ he said.

Then he stood before me and raised an oily palm as if in benediction. He patted me lovingly on the head and left the Sudsarama sanctuary, making his procession into the freshly blessed city.

Would you like to know more about this story? Check out my behind-the-scenes post on Patreon.