It’s one thing to design the mysteries. It’s quite another to keep them hidden.

Guarding their secrecy was my task, and for a while I took it very seriously.

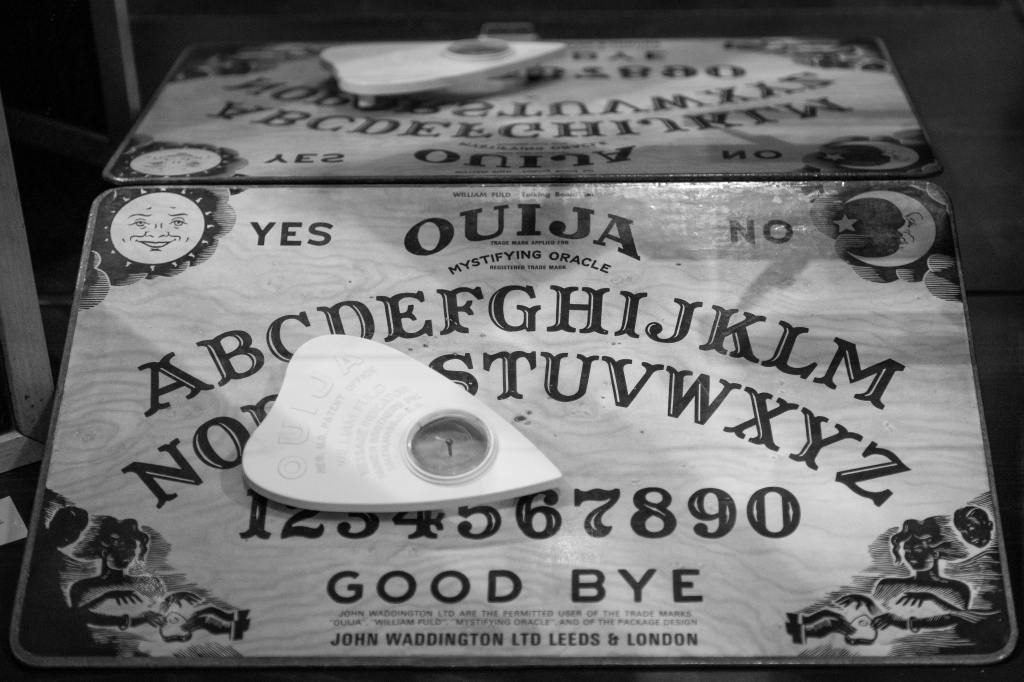

I’ve experimented with all sorts of methods over the millennia. Forbidden fruit trees with heavily guarded walled gardens, underwater cities, islands veiled by ethereal mists. I particularly enjoyed the secret societies with their hierarchies of esoterica, the self-important initiates, the chanting, the rituals.

I got bored with it all in the later years. I knew my complacency had gotten the better of me when I spotted an unsecured grimoire on an open shelf of a public school library. A frenzied scan of its contents revealed that the great human mysteries had been mass produced, unapologetically available to all.

The sacred voice. The holy trinity of personhood. The unmoved mover. The one in the many, the many in the one. The great wheel of time, the secrets to its turning.

In my panic I cast a spell on this and all grimoires of its kind. Let all who approach the contents be made to feel stupid or ashamed. Let all who already grasp this wisdom suffer vanity, smugness, self righteousness. Let it be excruciatingly boring.

Henceforth the grimoires became grammars.

Produced in haste and out of necessity, the strategy has proven my most effective yet. The great human mysteries remain hidden in plain sight.

Would you like to know more about this story? I talk about in in Episode 89 of Structured Visions, ‘Grammar as a gateway to mystery’. Subscribe to the podcast on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen.