Let me tell you something about the Earth’s Architects.

Folks accuse them of being arrogant.

But I say, take one look at that gorgeous globe from anywhere in the solar system and try to tell me it’s not the picture of perfection. Exquisitely balanced, it’s an aesthetic masterpiece, teeming with its plethora of enchanting life forms—from the industrious beaver to the whimsical bird of paradise—all delighting in their symbiotic dance.

The Architects didn’t design the humans, of course. They subcontracted that job, and by some minor miracle, yours truly got the bid.

My competitor’s prototype was unequivocally superior. His design was of creatures with a built-in appreciation for the mathematical precision of the world they inhabited. Humans would be thinkers, numbers folks. Appreciators. They’d spend their days noting the sequences that governed the patterns of petals on a rose, admiring with awe the symmetry of harmonics in the song of a blackbird.

His presentation intimidated me not a little. It made me reckless.

‘If I were you,’ I told the Architects, ‘I’d go with Numbers Guy.’

I said it right off the bat, before I even started my pitch. Then I waited for one of them to take the bait.

‘Why?’

‘Dude comes in here and tells me he’s invented a whole species wired to admire me? How could I resist? That said, you’re speaking to a raving narcissist, if you believe what my ex tells her lawyers.’

I produced a conspiratory chuckle as I let what I was saying sink in.

Then I got serious. I told them it wasn’t maths they wanted in the new humans, but language. ‘A new language,’ I said, ‘one made just for them.’

What would be the point of that? they asked. They didn’t trust me, but they couldn’t ignore me either.

‘Numbers are for getting to the essence of things,’ I explained. ‘Language is for covering things up.’

And why would they want the beauty of their world covered up?

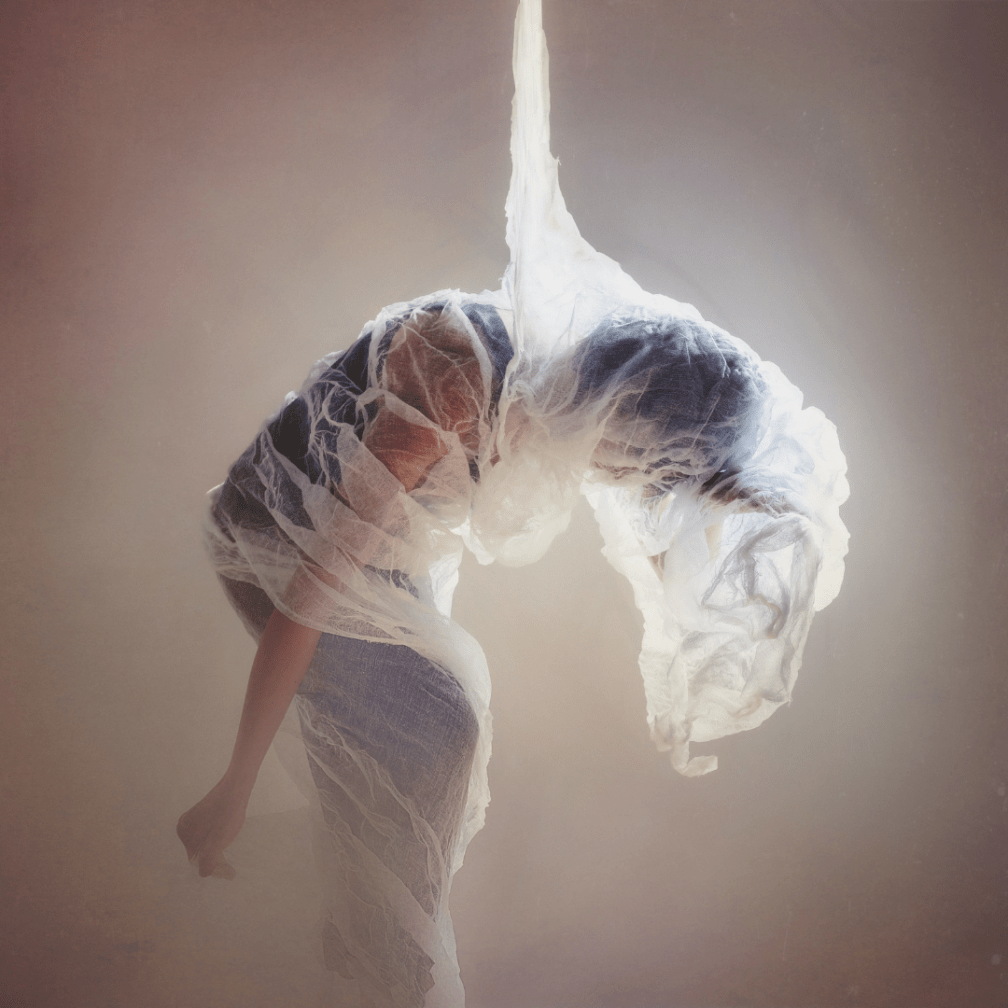

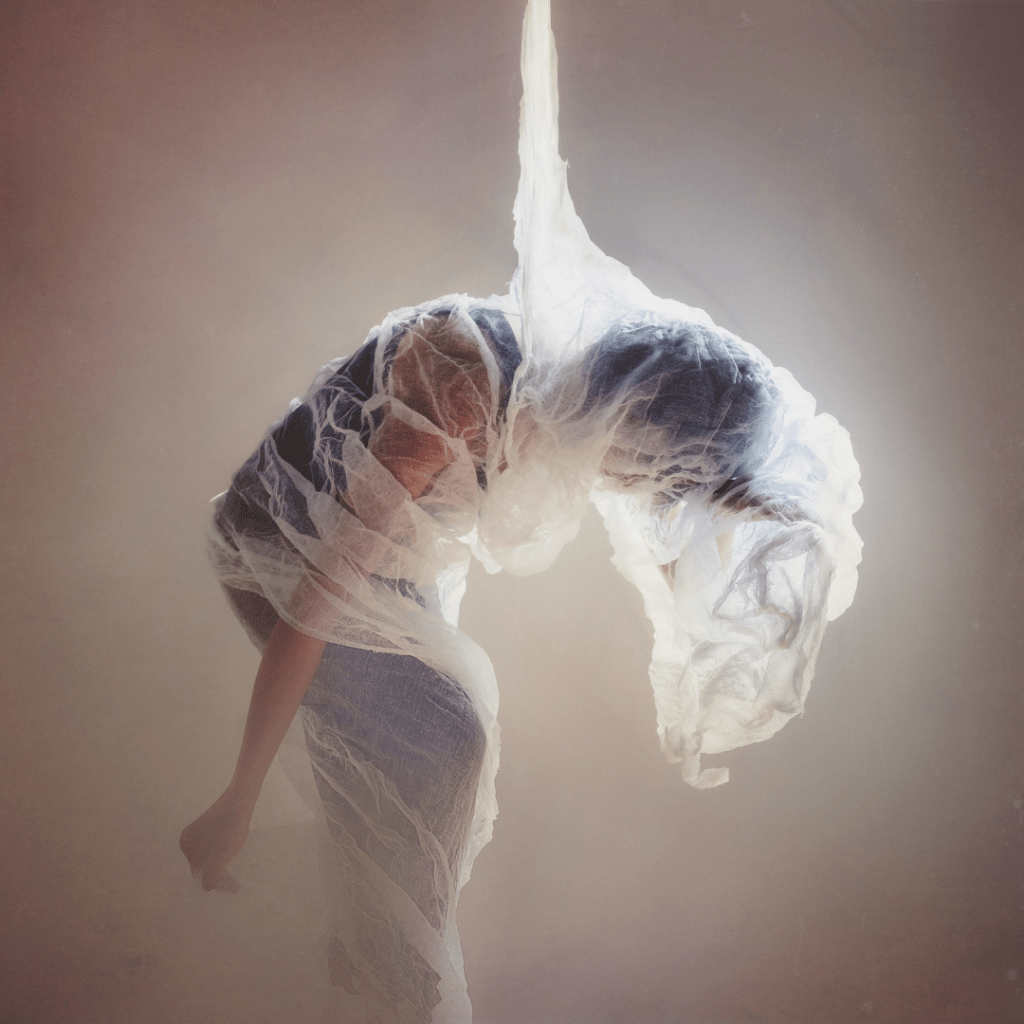

Language is a fabric, I said, like a drop cloth for an artistic masterpiece, that protects and preserves. Language is an insulating blanket. Supple and sinuous, it will respond to the ever-shifting shapes of the Earth’s aesthetic genius.

Language is the icing on the cake, I would have said, but by that point they’d given me the bid.

They’ve regretted it ever since, but they didn’t write an escape clause into the contract so they’re forced (or so they think) to watch the perfection of their world get corrupted by human language.

Language (they complain) produced the great cover up, the mechanism by which humans have obscured the Earth’s genius, lied about it, separated themselves inexorably from it, and in doing so, instigated its destruction.

If they were ever to consult me again (and of course they never would), I’d tell them to look closer.

The fabric of language does more than cover things up. It also folds over on itself, creating wrinkles, pockets, pouches.

One day—great magician that I am—I’ll pull a gold coin from one of those pockets, and the Architects will realise it was never a mistake.