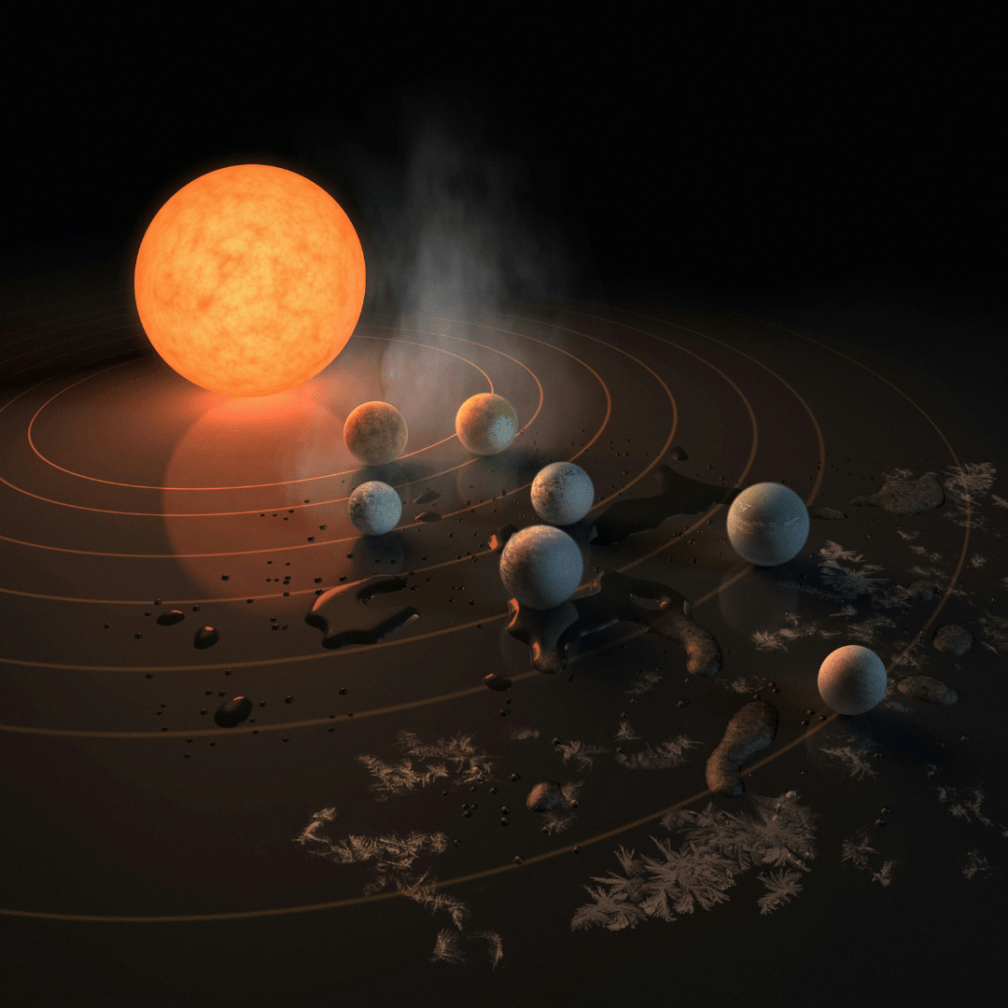

Corcoran and I went alone to planet F in the ELLPH system, where microbial and plant life had been discovered. The mission was to discover a proto-language. If F developed similarly to Earth, its vegetation would produce the early stages of the desire for separation, which would evolve into what we call human language, to be adopted eventually by hominid-like animals once their brains developed the capacity to house such an innovation.

The army didn’t approve of two men alone on this special op. The risk of romantic attachment in such a lengthy, close-quarters critical mission was too high. But Corcoran was the only one in the training who met the essential requirement, so he was the only one who could go with me.

I didn’t notice anything special about him at first. A stocky, Midwestern fresh-faced kid, eyes wide as saucers. Strong Minnesotan accent, but only when he spoke English. His Portuguese, French and Russian were radio perfect in pronunciation, but in syntax and vocabulary he fell behind the other shortlisted multilinguals.

It wasn’t until he referred himself for a psych eval on the selection exercise in Yucatán that I took notice of him.

‘What part of your psyche needs evaluating, Sergeant?’

‘I’m seeing fairies, Sir.’

A Mayan medicine man had led the unit in a ritual the night before. I suspected half of the men in the unit had caught a glimpse of the fae, but Corcoran was the only one admitting it.

‘That’s the psychedelics talking, Corcoran.’

He didn’t stop admitting it, even after I gave him an out. He believed they were real.

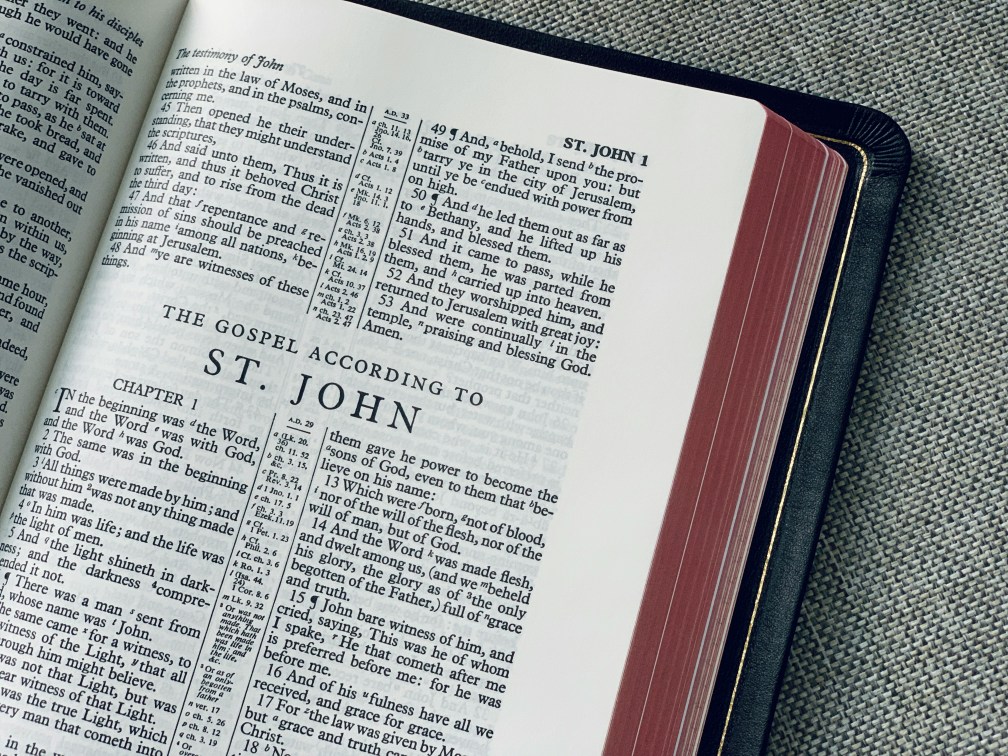

‘You were right about the fairies,’ I revealed on the craft that would bring us to F. ‘We’ve discovered that the elemental forces that on Earth are known as fae—or Alux, among the Maya—are the first attempts of a planet to produce linguistic expression.’

You were right about the romance, I’d have confessed to my superiors, if we hadn’t lost contact with them shortly before arrival. The elemental language prototypes that abounded on F had brought tears to the scrying pools of Corcoran’s eyes.

‘The separation creates the Mystery,’ he breathed. We held each other, weeping. The curious fairies gathered round.

Would you like to know more about this story? I discuss it in Episode 110 of Structured Visions, ‘Clap if you believe in fairies.’ You can also sign up to the Grammar for Dreamers newsletter to get monthly updates on the ideas that inspire my work.